What is a Field?

In physics, a field is a two or three-dimensional region that has a specific and measurable value at every location. It’s not necessary, or even logistically possible, to measure the value at each location, but a measurable value exists at every position.

Vector Fields

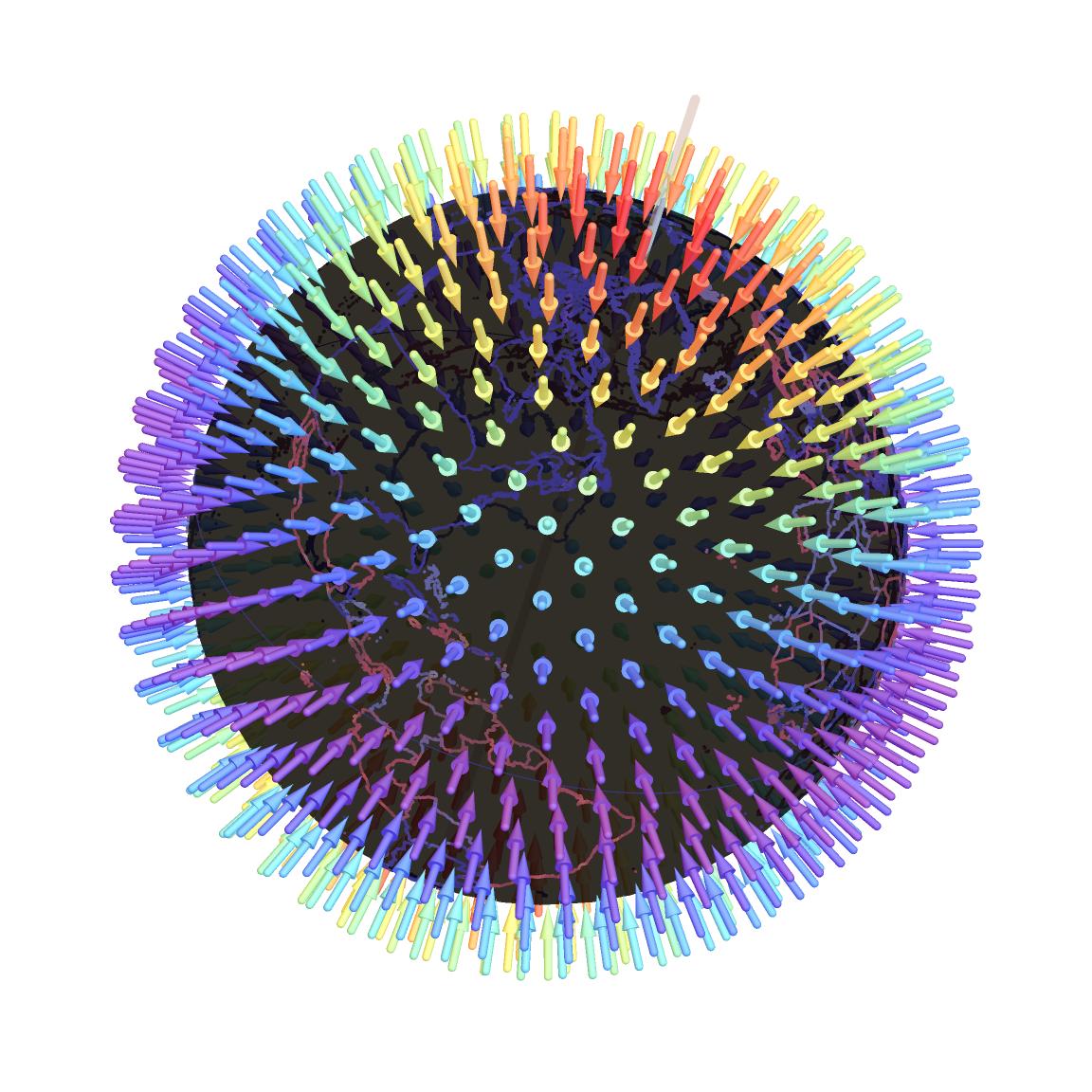

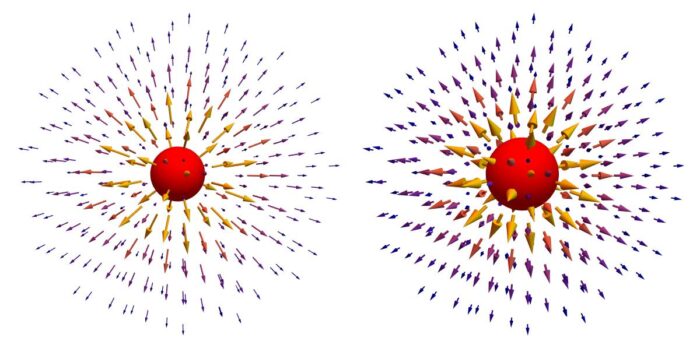

While colored arrows make for a visually interesting graphic, it is impossible to do any sort of meaningful math with colors. The magnitude of the acceleration needs a different graphical representation, and the obvious (and perhaps only) answer is to use the length of the arrows to indicate the magnitude of the acceleration,

The question “Is there gravity in the physical space around a single massive object if there are no other objects nearby?” is similar to the question “If a tree falls in the forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?”

These metaphysical questions make you momentarily stumble because each question takes advantage of innate assumptions about interaction and then removes a necessary second object from the discussion. A better question might be “Does the region of space around a massive object have different object properties than if that massive object wasn’t there?”

The answer is yes – the region of space around the Earth certainly has different properties than if the Earth wasn’t there.

Proof that Mass Alters Space

In Einstein’s Theory of Relativity, massive objects distort space and time.

Einstein’s theories are backed by astronomical observations. Large masses can alter spacetime and warp the path of electromagnetic waves to create a gravitational lens that alters the path of light in a similar way that a galaxy-sized optical lens would.

Einstein also predicted that any information about changes in the location of our imagined object or the position of Earth propagates outwards at the speed of causality (the speed of light 3 x 108(m/s)).

Mass does alter the properties of space-time, and when the mass moves, the information travels outwards at the speed of causality. It takes some amount of time for the changes in the field configuration to propagate outwards.

In September of 2015, scientists confirmed this portion of Einstein’s relativity theory when they detected gravitational waves caused by two colliding black holes.

Physically, there is of course a difference between electromagnetic and gravitational fields. But the underlying mathematics is quite similar.

Electric Fields

“Does the region of space around a charged object have different object properties than if that charged object wasn’t there?” is a more difficult question to answer than the question about mass and acceleration due to gravity.

From the day you were born, you’ve experienced the effects of Earth’s gravity first-hand. But you seldom experience the effects of electrostatic attraction and repulsion.

Electric charge is a mutable object property. Objects might possess a positive charge, a negative charge, or a net-zero charge at any moment as they acquire and lose excess electrons. That makes the behavior of the objects non-uniform: objects sometimes repel; objects sometimes attract; objects sometimes don’t interact at all.

But outside of carefully designed experiments, or when large amounts of electric charge are accidentally stored on your body as you walk across a carpeted floor, there aren’t very many opportunities for you to experience an electric force in your day-to-day life. That means it is difficult to develop intuition about the behavior of charged objects. The closest analog might be playing with magnets.

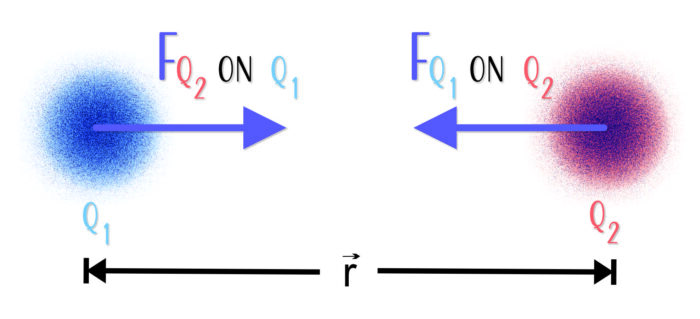

While you do need two objects to experience a force, you only need one object to perturb a region of space. Mass is an object property that perturbs space in one particular way. Electric charge is an object property that perturbs space in a different way.

The idea that space is altered by the presence of a charge is the basis for the idea of an Electric Field.

Electric fields exist in a region of space around a charged object. The field for a single charged object is given by the equation:

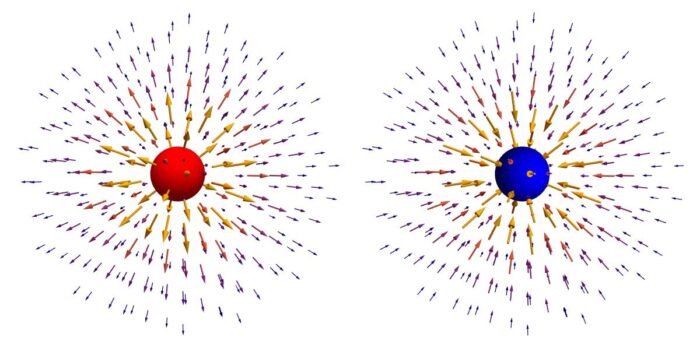

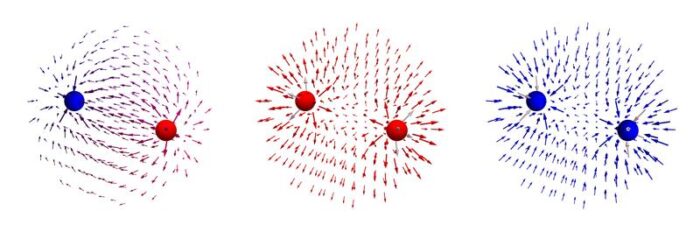

Since there are positive and negative charges, field vectors can point towards or away from the charged object. By convention, vectors point away from positive charges and towards negative charges.

The electric field intensity increases as the charge increases and the electric field intensity decreases as you move further away from an object.

Electric Field Around Multiple Charges

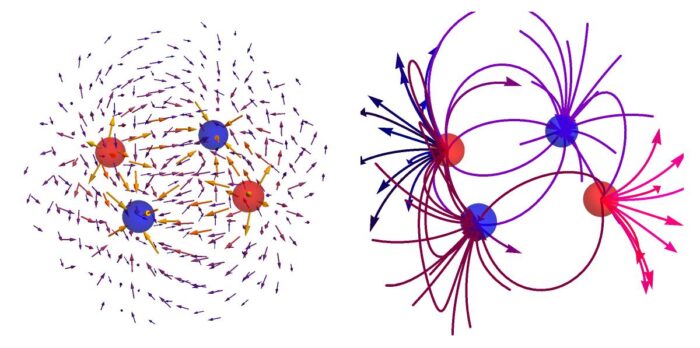

By convention, electric fields start at positive charges and end at negative charges.

This image shows the three possible charge pair scenarios. On the left, electric field arrows point from positive (red) towards negative (blue). In the middle, the positive charges repel and on the far right, the negative charges repel.

And since drawing all those little arrows can be cumbersome and confusing, it’s far more common to see continuous lines that extend from one charge to another. It is important to remember that these lines do not show the path that charges take from point to point, they are just simplifications of a potentially overwhelming vector field plot.

Electric fields are not electric forces. But they establish a mathematical and physical framework in a region of space should additional charges appear. As soon as another charged object is brought into that region of space where the first charged particle exists, the charges will interact and experience a shared force.

Summary

Hopefully, this blog has joggled enough neurons that some of your college physics is rushing back to you. Here are the important points: fields are mathematical models that define the magnitude of a particular object property at all locations in space; changes in the field propagate outwards at a fast, but finite speed; and, field-lines are shortcuts that allow us to avoid drawing an insane number of vectors.

In the next blog in the series, we’ll take a look at charge polarization.